Depending

the old brag of my heart, sweetheart

Nightmares. Or not. Wake up. Do some work if you can for a few hours, depending, or rock back and forth until the morning agitation dissipates, depending. Have a phone call, depending.

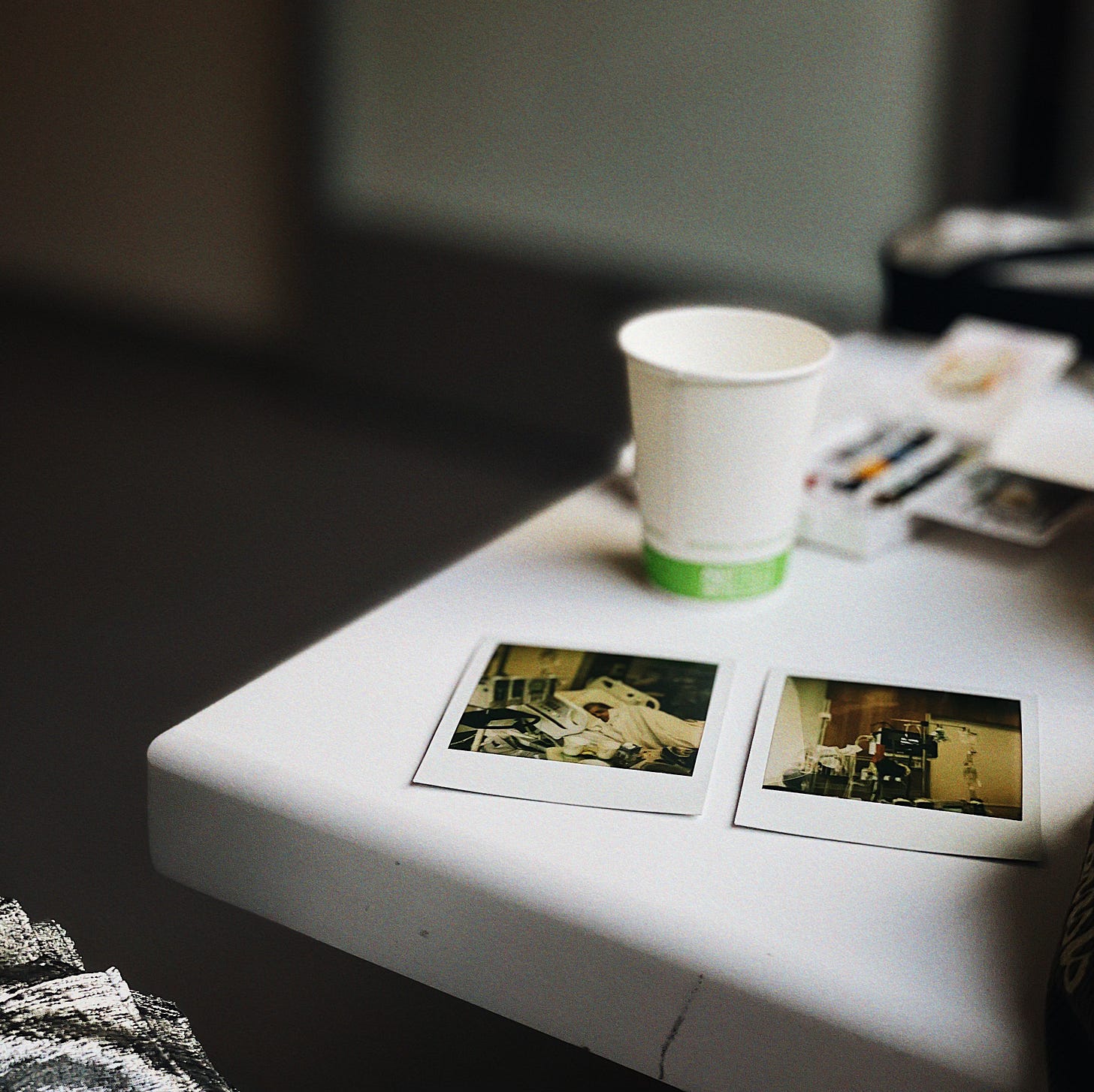

Then: the drive to the hospital. Hospital. Hospital. Hospital. The same route: front doors, elevator down a floor, turn right past the endless, unused hospital beds. A left at the elevators, another left at the elevators to his unit. Three sets of vacuum-sealed locked doors to protect the immunocompromised patients. Turn left. He's in there, in a bigger room than he used to be in (thanks to one of his favorite nurses). You open the door without knocking. This is likely some kind of violation, but it's become a habit. You like surprising him. Modesty, privacy, and secrecy are not so much things that are present in the hospital.

It's the sixth week. When will he be discharged? What exactly is wrong with him? How can they fix it?

We don't know, we don't know, we don't know. You always knew that medicine was fallible and lacking; now you know it even more than you used to.

Your favorite place, during the many hours you spend visiting, is curled up behind him (big spoon, your default position) on the hospital bed. It reminds you of when you'd sleep in extra-long twin beds together during college—not enough space, but it doesn't bother you. When you begin to feel a tug of sadness in your chest, you tell him the story of how you first met, as if he didn't know it already. But it's a comfort to think of it. You were two barely-formed humans, aged 18 and 20.

"How long have you been married?" asks a nurse one afternoon.

"We've been together since 2001," you say. For some reason—you were married in 2009—you're struggling with the math.

"Fifteen years," he says.

"Yes, fifteen," you say. "I used to actually be good at math. Now my brain has had it all shoved out by other things."

Depending, you doze.

Depending, you both doze.

Depending, you: paint birds; see scrub jays out the window; laugh; make silly jokes; become indignant about something a doctor or nurse has said; sing karaoke songs from YouTube; watch him get a bone marrow biopsy.

"Do you think I'll ever get to leave the hospital?" he asks.

"Yes," you say.

"I miss Daphne," he says, referring to your dog.

"She misses you too," you say.

"How is C?" asks your friend one night. It's the first time you've seen her in months. It's not the first time you've been asked this question, not at all. You never know what to say. "It could be worse," is what you always want to say.

Of course, it could always be worse, couldn't it?

It could, it could, it could.

Depending.

Depending.

(Depending.)

Hello. This is me, Esmé. It is a difficult time for me and my family right now. If you’d like to subscribe to REASONS FOR LIVING, which is ordinarily not so focused on hospitals, please do so; if you’d like to support me and my family with a paid subscription. please do so (I’ve lost many paid subscribers recently, which I understand—of course, it’s disheartening). Please take care of yourself and your loved ones today as best as you can, and always.

I’m on the same boat as you, Esme. My sister’s been in the hospital for roughly the same amount of time. Your piece resonated. Big hugs to you.

This is so beautiful. I think about you (both) all the time. Sending every ounce of love.