Erasure

what we do with our former selves, our former lives

When my mother was twenty-one and married my father, who’d wooed her (or tricked, as she describes it, by pretending to be an architect when he turned out to lack a single artistic bone in his slender body)—my mother, who was one of the most beautiful women in Pingtung, took her stacks of carefully kept journals and incinerated them all.

Her reason for burning her journals was twofold. First, she was beginning a new life as a married woman who was moving to America. Second, and I believe this to be the true reason: she did not want her new husband to know her youthful secrets. But I often think of those piles of books in a bonfire as the cremation of my mother’s younger self, with the pages held in high, licking flames crinkling as they turned her secrets to ash. I know she now regrets it. But burning all of your journals isn’t something you can take back.

She did start afresh in more than one way in America. Upon arriving in Michigan, my mother kept new journals about her American life. She explained them to me as mostly exercise workbooks; she was practicing her English. But the poignancy of that writing does not elude me.

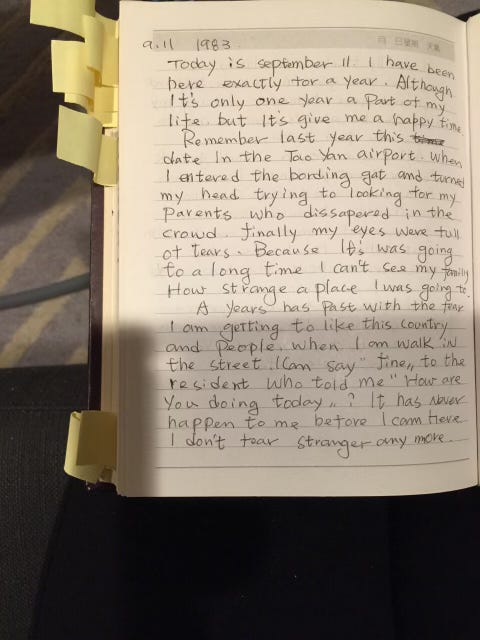

Here, for example, is her journal of December 1983, the year that I was born. She writes (with errors intact):

Today is September 11. I have been here exactly for a year. Although it’s only one year in a part of my life but it’s give me a happy time. Remember last year this date in the Tao Yun airport. When I entered the boarding gate and turned my head trying to looking for my parents who disappeared in the crowd. Finally my eyes were full of tears. Because it’s was going to a long time I can’t see my family. How strange a place I was going to.

A years has past with the [tear/fear]. I am geting to like this country, and people. I can say, “Fine,” to the resident who told me, “How are you doing today?” It has never happen to be before I came here. I don’t fear stranger any more.

When Trump was president, and C and I felt fear about what it would mean for us to stay in the country, we would talk about immigration. It was C, whose family has lived for generations in New Orleans, who was the most invested in the idea of leaving. One of his childhood friends had married a Black woman and was afraid that their family, which included their biracial child, was faring poorly in the U.S., and so they went to Canada, as so many Americans had imagined doing. But I couldn’t fathom doing what my parents had done, and what so many of my friends’ parents had done. Your parents made themselves foreigners for you, a friend once wrote to herself, and those words have haunted me since. My parents made themselves foreigners for me, and I couldn’t imagine myself being as brave. C has never not been American. The idea, for him, of immigrating to another country is something to imagine. For me, it’s in the handwritten words of my mother in a lined notebook as she practices her English. How strange a place I was going to.

Over the past few years, C and I have attempted to declutter our home. Much of what I end up sifting through are notebooks and journals; though not all of them are crammed from cover to cover, I still have hundreds of hand-filled books that someone, someday, will have to deal with. I have a note in my Drafts app, copy-and-pasted from a friend:

Hey, Es. Order one of those fireproof safes for your journals now (make it a waterproof one b/c it is the water post-fire that will kill them) and then give someone the second key and assign them to burn your journals without reading in case of your death. Journo friend I know has done something similar with safe and has assigned someone this duty, even tho certain of their materials are going to a college library, etc. The journals are to be destroyed by a trusted friend (not partner b/c maybe it's too much?).

Even with these exacting instructions, I haven’t taken the steps. How many fireproof safes would I need, exactly? If I somehow end up with a significant literary legacy, which journals would be important, and which would be junk? Who decides? I love reading Sontag’s lists, which are often nonsensical but reflect the cadence of her brilliant mind. One of the most comforting books that I turn to, habitually, is Plath’s unabridged journals, which include a lot of complaining—about her head colds and her fights with Ted, about her contemporaries who have won this prize and that prize, about being broke and a poetess in mid-century America.

Only recently have what are considered Plath’s “full letters” been published in thick volumes, and these letters give a very different view of the infamous Hughes-Plath marriage. The New Yorker says of the letters: “….They are among the most revealing pieces of prose that Plath ever wrote, in any genre. In them, she alleges that Hughes ‘beat me up physically’ a couple of days before a miscarriage, ‘seems to want to kill me,’ and ‘told me openly he wished me dead.’ In a foreword to this volume, Frieda, who was not yet three when Plath killed herself, maintains, ‘My father was not the wife-beater that some would wish to imagine he was.’”

The truth is somewhere, perhaps, between the lines. Burned, buried, lost, published: the art lives in whatever slips through. Whatever isn’t erased.