I Was a Childhood Magician

assistant, really—but who's counting

As a child, I could turn paper into dollar bills and water into grape juice. I could make a ball, signed by you with a Sharpie, disappear and reappear across the room. I knew what your card was with my eyes closed even though I let you shuffle. I knew your secret word as long as you wrote it down and let me handle the crumpled paper.

I was a Taiwanese American girl with a noxious home perm and too-big glasses, perpetually overdressed in the way that immigrants' children often are. I never performed my tricks at school—what if I tried, failed, and drew ridicule? At home I watched and rewatched our VHS tape of David Copperfield walking through the Great Wall of China. I would not visit the Great Wall of China, myself, for another decade, and by then had forgotten David Copperfield in all black with a white towel, caressing the Wall as though it were one of his honey-tanned and busty assistants, but in the mid- to late-80s I was fascinated by Copperfield: not his aesthetic, or his Phil Collins background music, and certainly not his broody good looks. I only wanted to be able to do what he did. My mother, in watching David Copperfield soar over a crowd in one of his most famous illusions, confessed to me that she thought he might actually be an angel.

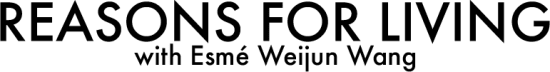

In fifth grade my best friend Jennifer was an occasional assistant to a local magician, a high school boy named Cameron who was primarily hired for local parties. But Jennifer fell ill, and with a forthcoming birthday gig coming up, Cameron didn't have a substitute for her; Jennifer volunteered me, and I was more than happy to comply. It made sense, after all, for Cameron to have a back-up assistant. What doesn't make sense to me, decades later, is why no one thought it was strange for a high school-aged boy to have not one, but two elementary-school-aged girls as his spangled assistants.

Cameron and I spent a day together so that I could learn how to assist with the tricks. Before he revealed the machinations of a single one, I had to promise not to tell anyone how they worked, including signing an NDA-like document that cemented our deal. I took this promise seriously. To this day, I have never told anyone, not even my parents, who still jokingly ask me to tell them the tricks behind the tricks. I keep myself from telling them not because of any loyalty to Cameron, but out of loyalty to magic itself, which has lost its shine in the last few decades, and might hold onto a bit of glamour if only I can hold onto the secrets behind even the most ridiculous, obvious illusion.

The most significant of Cameron's tricks was the big finale. I handcuffed him and tied him in a velvet bag, which was inside of a trunk, which was padlocked. I stood on top of the trunk with an enormous velvet cloth, tossed it into the air, and traded places with him in an instant. I loved knowing that we could do this, that I could do this. I politely said no when he asked me to caress his body the way that David Copperfield's assistants caressed him; there was nothing so obvious as "harassment" or "molestation" in my mind, but only the icky feeling that he wanted me to do something adult that I did not want to do. He seemed off-put by my refusal. He argued that I was being unprofessional, but didn’t insist.

The wind was terrible on the day of the only birthday party at which I ever performed, and half of the tricks were nearly given away. But for the big finale we switched places in the trunk without anyone seeing how it was done. The children clapped and cheered while I, curled up inside the velvet bag, felt a rush of joy run all through me.

Years later, in my early 30s, a friend and his wife had me over to their New York apartment. In exchanging anecdotes the woman told me an outlandish-but-believable story about being convinced to stay with David Copperfield for a weekend on a private island. In the story he comes off as lecherous, if not worse—an aging magician who still has the power to coerce models and almost-models to come away with him, and then to let him do what he wants with them. With magic, what I had always wanted was the power not to hurt anyone with the ability, but to decide what secrets I wanted to keep, and to keep them for as long as I wished. Unlike other secrets that I knew to keep as a child, the unknown quantities involved in illusion-making never burned me from the inside, but would simply allow me to drop through the trap door in the trunk and never tell anyone it existed; or at least, not until it felt like freedom to do so.

Introducing: The Book Proposal Kit

How does one go about writing a book proposal? What are agents and editors looking for in a book proposal that sells, resulting in bestselling books? Included in this kit are the following: a book proposal template, hourlong video class, and two sample, successful book proposals—putting you on the road to the book deal in your future.

"In two books and two agents, I have NEVER been schooled as hard or as well on the craft of writing an effective book proposal as I was by Esmé Weijun Wang. Esmé has an unfakeable passion for making practical, actionable information available to writers to ALL writers, at all career stages and backgrounds, living and working with all kinds of limitations. Her warm, inclusive teaching style offers a priceless act of service to the literary community.”

—LAURA G.

Thank you for reading The Unexpected Shape with Esmé Weijun Wang. This post is public, so feel free to share it.