Reason for Living #11: Scandoval

the gift of petty drama

10% of the proceeds from each REASONS FOR LIVING newsletter go to an organization of the guest essayist’s choice. I’ve chosen NMDP (formerly Be the Match). NMDP is a global nonprofit leader in cell therapy, helping save the lives of patients with blood cancers and disorders.

Please consider donating here. And if I might implore you to do take one more step, please consider signing up for the registry, especially if you’re a BIPOC person (there are far fewer BIPOC donors currently in the registry). It takes no more than mailing in a cheek swab, and you could save a life. Someone took that step, was a match for C, donated their bone marrow (a relatively simple procedure), and saved his life.

If you enjoyed this free edition of REASONS FOR LIVING with Esmé Weijun Wang, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers receive two bonus personal essays from me per month. We have monthly Fireside Chats, which are gatherings to discuss, play, and learn about creativity and limitations. Finally, you’ll receive access to our amazing Creative Resilience Toolkit. Paid subscriptions also help me to pay the bills, as my chronic illness and disabilities prohibit me from working a standard job, and both my husband and I are dealing with chronic illness as he recovers from cancer.

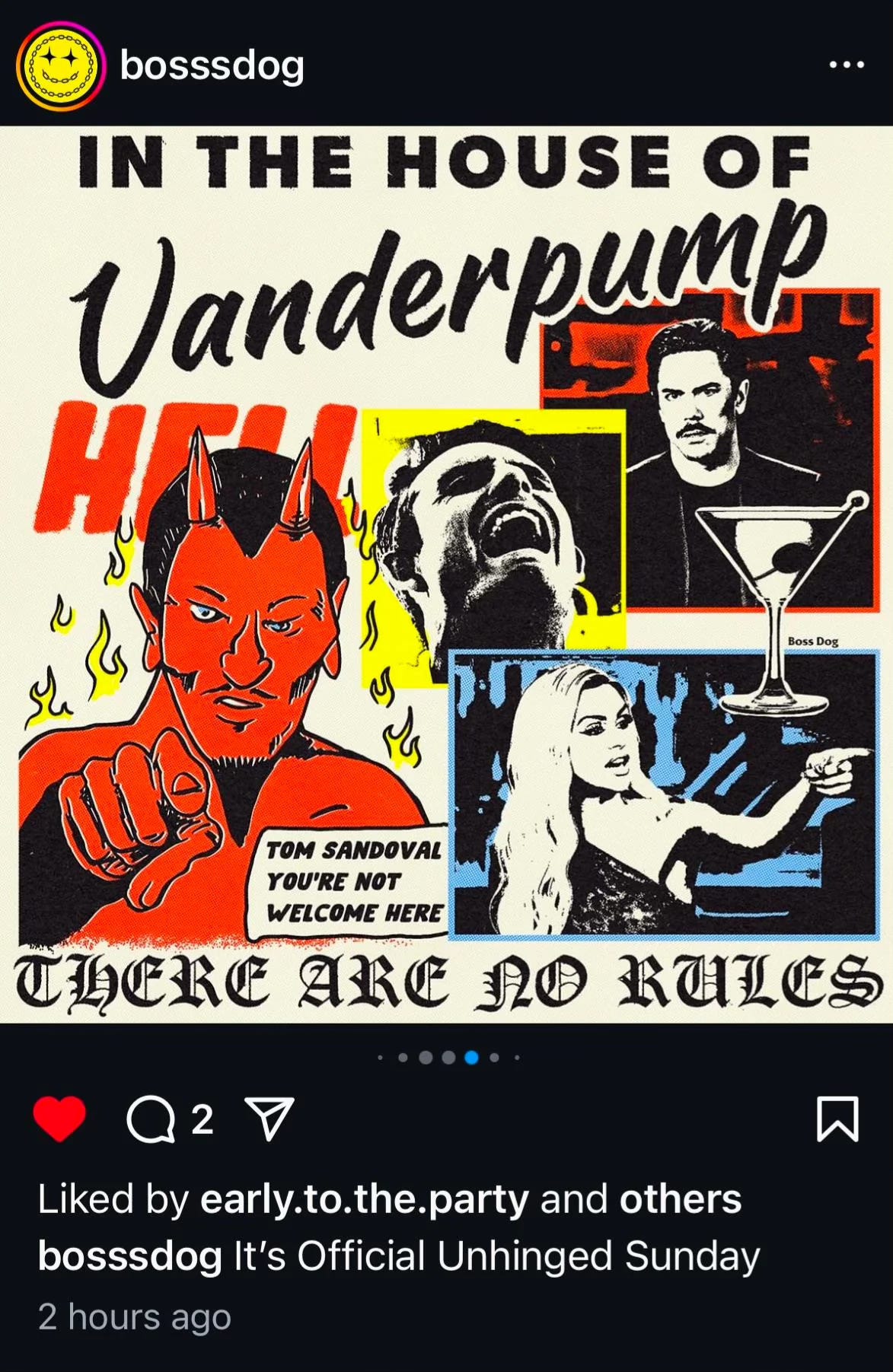

I discovered "Vanderpump Rules" when I needed it most: Scandoval. Not because I cared particularly about reality TV infidelity, really—I’d dabbled in “The Bachelor,” but knew little about the ongoing chaos at SUR. (For those of you who don’t know much about the Vanderpump universe: all you really need to know about the reality show’s vibe is that SUR stands for Sexy Unique Restaurant.) Yet as the internet exploded with theories about the sordid affair between Tom Sandoval and Raquel Leviss, my husband C was in a hospital bed, recovering from mysterious complications resulting from cancer treatment. This confession feels both trivial and transgressive, as though by admitting that amid profound personal crisis, I sought refuge in the manufactured drama of beautiful people working at a West Hollywood restaurant represents a failure of intellectual seriousness.

Yet here we are.

There's a peculiar intimacy that develops between caregivers and the media we consume during and between hospital visits. Every time I visited C in the bone marrow transplant ward, I brought along a galley of Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo; I still haven’t finished it. While sitting beside C's bed—adjusting his pillows, asking questions during rounds, willing myself to stay upright despite my POTS-induced exhaustion—I found myself devouring "Vanderpump Rules" on my phone, earbuds in, one eye always on C. In the earlier days of my own illness, I'd listened to Scandinavian crime novels while showering, finding strange comfort in narratives of bodies utterly destroyed when my own felt under siege.

"Vanderpump Rules" served a different function. Unlike the crime novels, “Vanderpump” offered something I desperately needed in that antiseptic hospital room: the suspension of consequence. No matter how ludicrous the betrayal, how loud and raucous the fight, how tearful the confrontations in the back alley of SUR, there was an unspoken agreement that all would be narratively resolved. There would always be enough togetherness despite the hectic angst, it seemed, to have another season.

When someone you love is recovering from cancer and your days are governed by medical protocols, there is profound relief in witnessing problems that are simultaneously catastrophic and inconsequential.

As C's hospital stay extended from days into weeks, and from weeks into months, the logistics of caregiving became its own full-time occupation. I started a GoFundMe to help secure housing near the hospital—a necessity when home was too far for easy daily visits and hotel costs accumulated with merciless triple, then quadruple, digits. I shuttled our dog Daphne between temporary accommodations, promising Airbnb owners that she’d only stay in her pen, whispering desperate pleas into her fur: "Please, just hold it until I can get you outside." The rhythms of my days were dictated not by filming schedules for the sake of portraying “reality” but by medication timings, early-morning doctor rounds, and the precious windows when I could crawl into C’s tiny bed and cuddle, reading George Saunders aloud to one another while we were interrupted by nurses with every other page.

As C recovered slowly—too slowly for both of us—I found myself oddly soothed by watching Tom Sandoval's spectacular inability to take accountability for anything during the Scandoval revelations. The sheer predictability of his narcissism, of his endless doubling down, became strangely comforting—a villain so committed to his villainy that he approached a kind of perverse integrity. When he insisted, despite all evidence, that he was actually the one suffering most, I laughed aloud in the hospital room, startling a passing nurse.

"At least I'm not these people," became my silent mantra, a thought I returned to again and again. It was a peculiar comfort, this comparison between their catastrophes and mine. Their problems seemed so chaotic, so messy, so incredibly emotionally devastating—and yet I was the one sitting in a hospital room, navigating life and death with C. The paradox wasn't lost on me: I found relief in watching problems that I felt were worse than mine, even as I faced something objectively more serious than anything that had ever happened at SUR.

My problems during those winter months were not dramatic in the reality television sense. They were the quiet, grinding difficulties familiar to anyone suddenly thrust into the role of caregiver, particularly when you yourself are ill: the creeping exhaustion, the constant vigilance, the management of limited energy resources while medical needs demanded more than I had to give. While the internet debated whether Ariana should have seen the signs of Sandoval’s seven-monthlong infidelity, I was learning to read actual medical signs, monitoring for infection and the hope of healing.

What "Vanderpump Rules" offered me was a parallel universe where problems manifested not as invisible struggles but as spectacular ruptures—public meltdowns, relationship implosions, friendships fractured over who was on whose side at any given moment. In one season, Stassi storms drunkenly away from her own murder-themed birthday party, leaving Kristen and Katie with the $1400 tab; she shows up the next day while they’re bedazzling their scooters. All is forgiven. These were problems that demanded witnesses, that couldn't be dismissed as "all in your head." They were gloriously, painfully, wretchedly visible.

For those of us sitting in hospital rooms day after day, there’s something oddly validating about watching people whose pain demands center stage, whose grievances command not just attention but thousands of viewers as well. Perhaps most importantly, their chaos reminded me that some problems—no matter how all-consuming they might feel in the moment—eventually pass, while others, like C's recovery, require the patience to endure what can’t be escaped through dramatic confrontations or tearful apologies.

During the height of Scandoval, when Ariana was offered free groceries by a popular store, she declined and requested they be donated to a food pantry instead. I remember hearing this on a podcast while shelling out for a samosa in the hospital cafeteria, struck by the vastly different economic realities between her betrayal and my caretaking. Ariana makes substantially more money than C and I do. She occupies a higher tier of public visibility. Her heartbreak generated not just sympathy but tangible offers of support—free makeup, clothing deals, Dancing with the Stars. She became the host of Love Island and starred in Cabaret on Broadway. Meanwhile, I had started my first ever GoFundMe, a public admission of need that felt both necessary and humbling.

But the GoFundMe met its goal quickly, faster than I had dared hope. Our community of readers and friends rallied around us with astonishing generosity. Each donation notification on my phone pierced me with simultaneous gratitude and guilt. After all, so many people need money. So many families face medical catastrophes without the cushion of a platform, without the ability to transform their suffering into a narrative that others can participate in through giving.

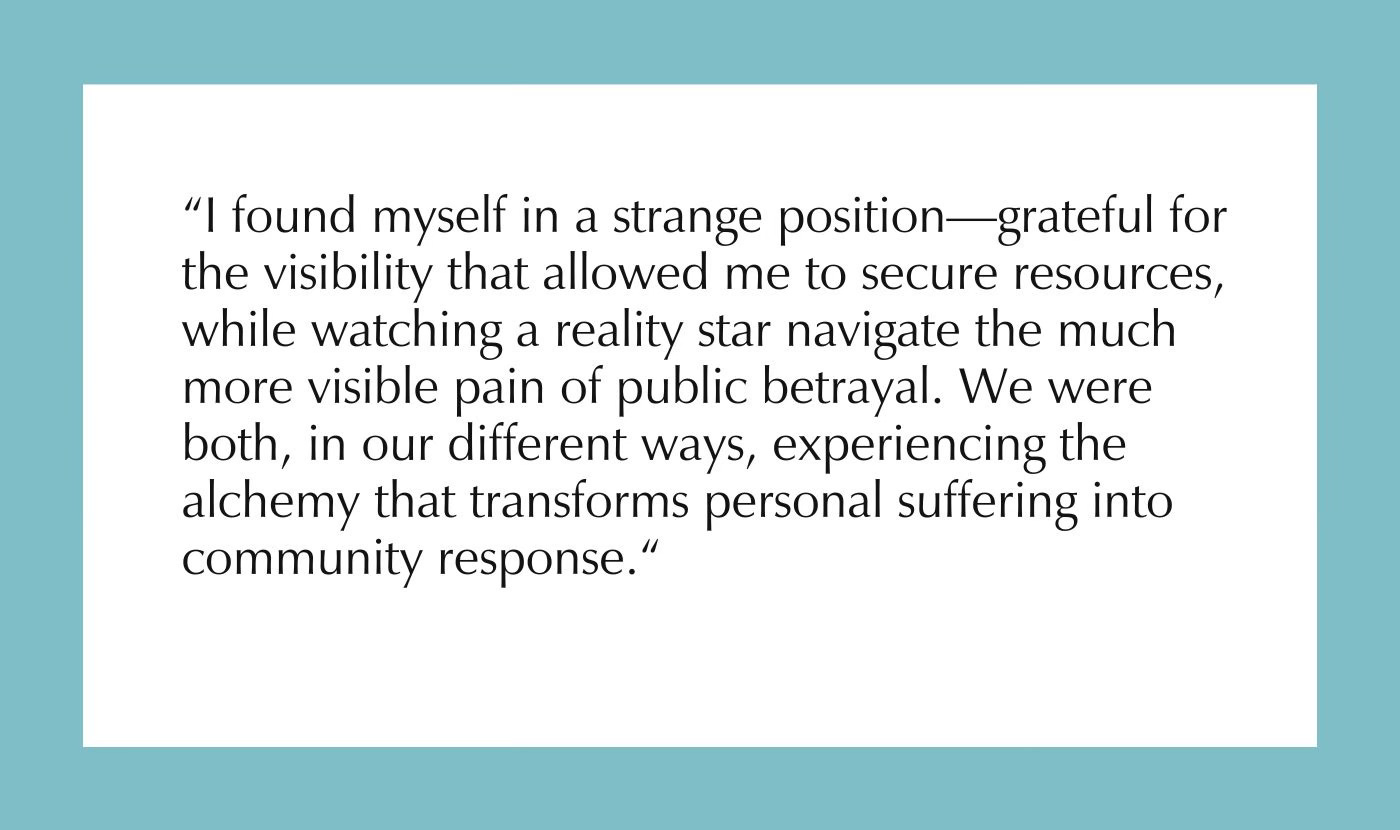

I found myself in a strange position—grateful for the visibility that allowed me to secure resources, while watching a reality star navigate the much more visible pain of public betrayal. We were both, in our different ways, experiencing the alchemy that transforms personal suffering into community response.

I sometimes wonder if my reality TV escapism represents a moral failure—if turning to reality television during a health crisis is akin to abandoning my post at C's bedside. But in those months of hospital visits, I came to believe that sometimes, survival requires strategic retreat. To engage meaningfully with the medical crisis before us, I needed to be able to run away through the tiny screen on my phone. On paper, cancer is objectively "worse" than infidelity. And yet, I sometimes envied the Vanderpump cast—their problems were explosive but ultimately resolvable, their pain performative but undeniably seen and registered by millions. Cancer, by contrast, is patient and indifferent. There's no reunion episode where everyone gets to air their grievances about how shitty cancer is, no producer to ensure a satisfying narrative arc for the story of illness. In a medical system that valorizes stoicism and sacrifice from family caregivers, sometimes the most radical act is choosing where to place your limited attention. For those managing the emotional labor of hospital days, this becomes not just self-care but self-preservation.

What makes reality television so satisfying is the guarantee of narrative resolution. No matter how chaotic the circumstances, viewers know that by the reunion episodes, everything will have been processed, analyzed, and at least partially resolved. The story is contained, edited for maximum impact, with clear villains and heroes who evolve according to reliable character arcs—and then we just have to wait until next season, when we’ll find out what happens next.

Illness offers no such narrative satisfaction. There were days when C seemed better, only to worsen unexpectedly the next morning. There were promising test results followed by concerning symptoms. Each time we thought we'd reached the final chapter of this particular health crisis, with the discharge date being pushed further and further back, a new complication would emerge, extending our story without commercial breaks or season finales. So when would our medical crisis reach its resolution? When would we know if we were in the redemption arc or the tragedy? The structured seasons of reality TV felt like a promise that endings do exist.

When I first began watching "Vanderpump Rules,” I kept it secret—a guilty pleasure I didn't advertise. But as the weeks of recovery stretched into months, I began to understand that my "unserious" comfort was essential infrastructure for handling the serious matters demanding my attention.

There's a tendency to dismiss reality television as pure escapism, but I've found that it functions more as a pressure valve—a carefully contained space where I can process emotional extremes. Watching Ariana scream, “I don’t give a fuck about Raquel!” allowed me to feel rage and grief vicariously, without directing those emotions at C's illness or the medical system, where such feelings would have been antithetical to his healing.

I don't know if "Vanderpump Rules" will be your crisis comfort show. Perhaps you'll find solace in "The Great British Bake Off" or "Love Island" or reruns of "The Office." What matters is giving yourself permission to need what you need without judgment or apology, especially when what life demands of you seems like an impossible slog. The unexpected shape of my own resilience included many things I never anticipated: hospital cafeteria routines, careful documentation of medication timing, strategically scheduled relief from other caregivers, and yes, hours spent watching beautiful people at SUR making terrible decisions that somehow, improbably, never quite destroy them.

In finding comfort where comfort presents itself—even in things like reality television—we’re not avoiding reality but equipping ourselves to face it with whatever resources we can muster.

And sometimes, those resources include watching DJ James Kennedy's screaming fits, both terrible and mesmerizing, while the hospital machines beep and beep beside you. In the space between life and death, between sickness and health, there are worse companions than people whose problems, however catastrophic they may seem, will be resolved in time for next season. ❤️

If you enjoyed this free edition of REASONS FOR LIVING with Esmé Weijun Wang, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers receive two bonus personal essays from me per month. We have monthly Fireside Chats, which are gatherings to discuss, play, and learn about creativity and limitations. Finally, you’ll receive access to our amazing Creative Resilience Toolkit. Paid subscriptions also help me to pay the bills, as my chronic illness and disabilities prohibit me from working a standard job, and both my husband and I are dealing with chronic illness as he recovers from cancer.

Infidelity

by Louis Untermeyer

You have not conquered me—it is the surge

Of love itself that beats against my will;

It is the sting of conflict, the old urge

That calls me still.

It is not you I love—it is the form

And shadow of all lovers who have died

That gives you all the freshness of a warm

And unfamiliar bride.

It is your name I breathe, your hands I seek;

It will be you when you are gone.

And yet the dream, the name I never speak,

Is that that lures me on.

It is the golden summons, the bright wave

Of banners calling me anew;

It is all beauty, perilous and grave—

It is not you.

Do you watch television for comfort? If so, what do you watch, and what do you think it does for you? Why do you think it’s that particular show that brings you comfort?

If you enjoyed this free edition of REASONS FOR LIVING with Esmé Weijun Wang, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers receive two bonus personal essays from me per month. We have monthly Fireside Chats, which are gatherings to discuss, play, and learn about creativity and limitations. Finally, you’ll receive access to our amazing Creative Resilience Toolkit. Paid subscriptions also help me to pay the bills, as my chronic illness and disabilities prohibit me from working a standard job, and both my husband and I are dealing with chronic illness as he recovers from cancer.

In my early days of postpartum I started watching the local news in the morning and wheel of fortune at night. Since I don't have cable, just a few random channels, it felt comforting to watch something that was happening live, with thousands of other people also watching, like I was a part of something no matter how small. Now five months in, I still do these morning and evening TV rituals. I don't need to focus too hard or think too hard about what I'm watching while I'm caring for baby. But I feel like I've gotten to know the local anchors on the news, Ryan and Vanna on wheel. I think what it comes down to is that it makes me not feel so alone when motherhood feels heavy.

When i didn't have other hobbys, i used to watch TV series, but not my hobby has become YouTube surfing (watching mostly videos about language, animals, and music groups). About a month ago, i finished watching "Dark" TV series. Philosophically speaking, it seems incomprehensible at first, but the love bonds between some of its characters have deep roots, and after reaching Season 3 (its last season), you understand it more clearly.